1. Introduction

This report looks at how IT Service Managers (ITSM) delivering IT as a service can generate and deliver value by using frameworks to design, implement, measure and improve a service portfolio. The discussion focuses around the Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) framework.

2. Value vs Waste

Barnes et al. (2009, p. 2) state that “Value is defined as the worth or desirability of a thing”. Traditionally, the IT value proposition revolved around supplying the correct technology for the job. However, as technology has become more widely implemented, decisions must be made upon saving people time, helping to make better business decisions or improving services. Value is subjective with differing viewpoints for example from company executives to IT managers, depending who is viewing it.

Barnes et al. (2009, p. 1) look at the definition of value within businesses stating that “Strategic positioning, increased productivity, improved decision making, cost savings, or improved service” are all ways value could be defined and that value is no longer simply just a financial concept. However, Walker (2016) stated “monetary cost is the only language businesses understand”.

Waste on the other hand is not desirable and the direct opposite of value. Waste can come from many factors and should be addressed by reviewing how services are managed and delivered. (Steinberg, 2016, pp. 6-9). Necessary waste is acknowledged by Walker (2016) examples being server redundancy, administration and data or service backups never used.

Driving up business value and driving down waste should be the overall objective for a successful ISTM. But, there are many factors to consider in attaining this goal.

2.1. Value Realisation

Value can be measured in different ways and companies take differing views on how to handle this. Barnes et al (2009, p. 3) recognise that companies will use Return on Investment (ROI) or Total Cost of Investment (TCO), Total Delivery Cost (TDC) others Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) or a selection. There is no single universally agreed measure of IT value. Hence it is important that IT managers are working alongside business leaders towards a common goal and IT is not viewed as segregated from other parts of the company.

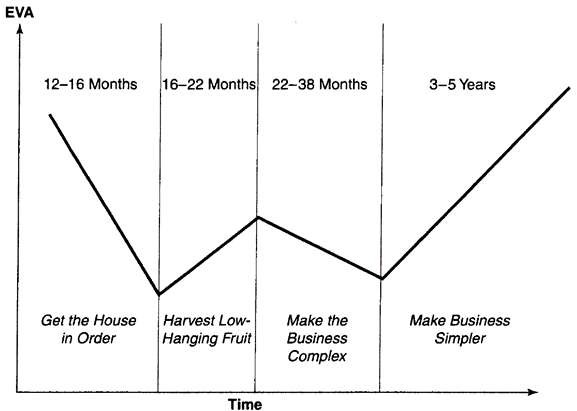

Barnes et al (2009, p. 4) go on to explain that the benefits of technology need time to come to fruition and the view of value can evolve over time. For this reason, many companies will experience a ‘W’ effect, Figure 1, when delivering IT value. Typically showing no benefits during the first twelve to sixteen months and only after this period are a limited number of efficiencies accomplished. Usage increase and complexity will normally occur and lasting benefits will only be attained by simplifying processes and implementing the use of technology, information and people more effectively.

In one case study into Campbells (Ross & Beath, 2008, p. 6), project Harmony took over five years to realise benefits and the case study of PepsiAmericas (Beath & Ross, 2010, p. 10), project Next Gen took over eight years. PepsiAmericas Ken Keiser is quoted as saying “Ten years ago, if our IT systems blew up, we could still run our business… Today we can’t… we could not operate without them”, clearly showing the integration impact IT has had.

Large scale change taking long periods of time are not the only type of change that an ITSM must deal with. Further discussion on change can be found later in this document.

3. Driving IT Value

ITSMs will often employ techniques to streamline the IT proposition. Frameworks such as ITIL are widely recognised and contain a set of best practises or guidelines. Unlike standards that have set criteria which need to be met and are often verified externally, best practise provides a skeleton that businesses can adopt and adapt to meet their needs taken from industries worldwide (Gallacher & Morris, 2012, pp. 1-4).

International Standards should not be ignored. As they provide significant advantages to business, helping to increase business reputation and operations. In a case study of Shuguang Hospital the International Organization for Standardization (2014, p. 9) state that “Since the transition … to the ISO 9001 standard in 2010, the hospital has made significant breakthroughs in every aspect of its operation”. Standards will often require businesses to change the way they operate, provide additional cost and add workplace pressure generated from external audits (Walker, 2016).

Several frameworks exist developed by various corporations and organisations some of which are listed below.

- ITIL

- IT4IT

- COBIT

Though, ITSMs may choose to employ none, one or be influenced by multiple frameworks and standards implementing the best fit for the business needs. ITIL focuses on three main elements, people, processes and technology. Not being specific to any one technology or industry type it can be applied to organisations of all sizes in any sector (Walker, 2016).

Gallacher & Morris (2012, pp. 4-5) suggest reasons for ITIL adoption might include:

- Creation of value for customers through services provided

- Emphasis on integration with the business

- Ability to measure, monitor and optimize IT services

- Manage the investment and budget for IT services

- Risk management

- Knowledge Management across service management

- Effective and efficient service delivery by management of resources and capabilities

- Standardised approach to ITSM across the organisation

- Relationship improvement between service provider and customers

- Coordinate delivery of goods or services and reduce costs

As technology is constantly evolving McKeen and Smith (2008, p. 72) point out that understanding where you have been and where you are going can be of huge benefit. Roadmaps coupled with architectural and departmental documentation can produce a more holistic overview of a company’s goals or objectives and “help ITSMs avoid making suboptimal decisions”.

McKeen and Smith (2008, pp. 74-75) also acknowledge that aligning IT with the business can result in the following:

- Achieving business goals

- Reducing complexity

- Enhancing interoperability of business functionality

- Increased flexibility

- Increased speed of implementation

- Responding to market changes

- Focusing investment

- Responding to legislation

- Consolidating global solutions

- Lowing costs

4. Strategy

ITIL Service Strategy (Cannon, 2011, p. 37) states that the goal of a service strategy is “superior performance versus competing alternatives” and suggests that having strategic and service documentation in place within a Services Knowledge Management System (SKMS) allows for innovation and change to take place in a more controlled manor reducing risk; with service strategy being devised from the four Ps:

- Perspective

“It describes what the organization is, what it does, who it does it for and how it works, and it does this in a way that makes it easy to communicate internally and externally”

- Positions

“Whether it is about offering a wide range of services to a customer, or being the lowest-cost option”

- Plans

- “Some plans are high-level, such as the overall strategy, while others are more detailed, such as the execution plans for a particular new service, or process”

- Patterns

“Ensure that the service provider does not continuously react to demand in a new way every time. Patterns enable the service provider to predict how a strategy will be met, and what investment will be needed”

Ross & Beath (2008, pp. 6-7) state that in 2002 Campbells Soup adopted the strategy to

“distinguish core business activities from non-core business activities, and to then manage non-core activities for low cost while managing core activities… for differentiation and growth.”

Interestingly Campbells (Ross & Beath, 2008, pp. 8-10) outsourced its IT infrastructure to IBM. By allowing IBM to provide this service it became mutually beneficial for both companies to grow and expand, allowing Campbells to focus internally. However, the study notes that “outsourcing infrastructure operations and other technical responsibilities would not necessarily be a cheaper alternative to running computer operations internally.” Walker (2016) expressed that caution towards outsourcing may be due to bad experiences or legal issues such as data’s geographic storage location.

Campbells (Ross & Beath, 2008, p. 10) demonstrated strong governance throughout, ensuring that everything undertaken was for the benefit of the strategy. This governance filtered down through all levels of project Harmony and by 2007 Campbells was “significantly outperforming industry averages”.

Strategy is also at the core of the ITIL service lifecycle.

5. ITIL Service Lifecycle

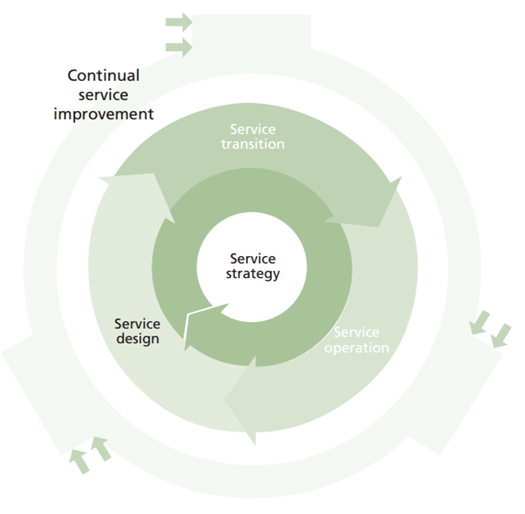

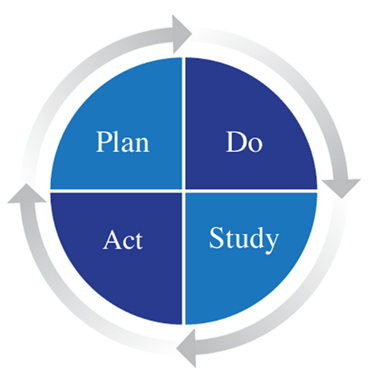

ITIL is set up as a continuous cycle of service improvements designed to work for the service strategy and focuses on ‘why’ something should be done before the ‘how’. ITIL outlines processes for the implementation of plans during the transition stages, monitoring and learning from the operation of the new service to make improvements where the learning is relevant (Steinberg, 2012, pp. 1-5), figure 2. Walker (2016) likened it to the Deming Cycle, figure 3.

It should be made clear at this stage that ITIL (Steinberg, 2012, p. 9) defines a service as “A means of delivering value to customers by facilitating outcomes customers want to achieve without the ownership of specific costs and risks”.

6. Service Design

There is the potential for many sources too consume services and ITIL (Steinberg, 2012, pp. 11-12) categorises them under two main headings

- Customers

People who pay for the service.

Define Service Level Agreement (SLA) and targets.

- Internal Customers

Work for the same business for example the accounting department

- External Customers

not associated within the same business as the IT service provider and will purchase services.

- Users

People who use the service day to day

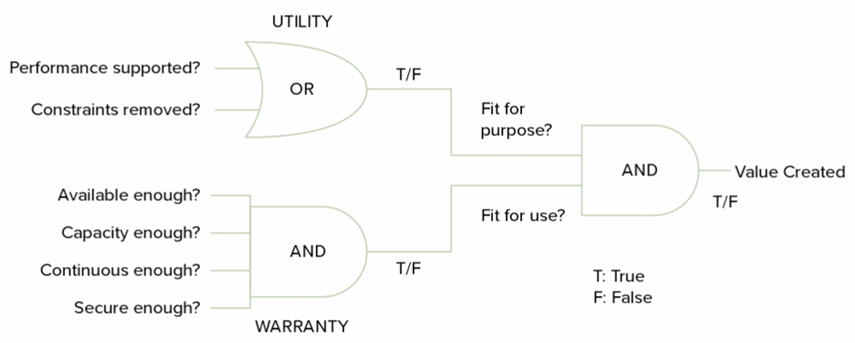

ITIL (Gallacher & Morris, 2012, p. 31) suggests that from the customer view of an IT service, “the value of a service is made up of utility and warranty”. Figure 4 demonstrates ITILs service design.

- Utility – Fit for purpose

Meets a need or enables the business to do something

- Warranty – Fit for use

Assurance a service will meet its requirements

- Can it facilitate the users at the correct times?

- Can it handle the volume of service requests?

- Can it provide reliable continuous service?

- Is the service secure enough to use?

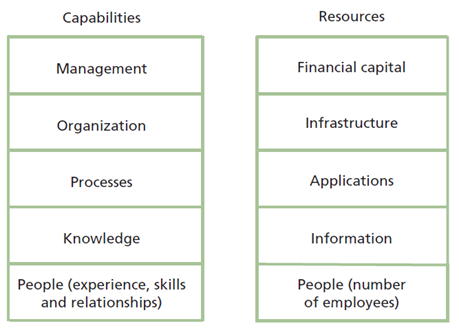

Before a service and its underlying processes can be designed further, process enablers, assets need to be considered. ITIL (Cannon, 2011) defines assets as “any resource or capability” and, if a company is lacking in either, implementation may not be immediately viable. However, it is easier to obtain resources than capabilities. Examples of resources and capabilities are shown in figure 5.

Asset roles with mapped accountability or responsibilities should be created and documented. The SFIA foundation (no date) provides a roles/skills matrix to help address this. Potentially identifying areas for recruitment or asset training.

7. IT Service Operations

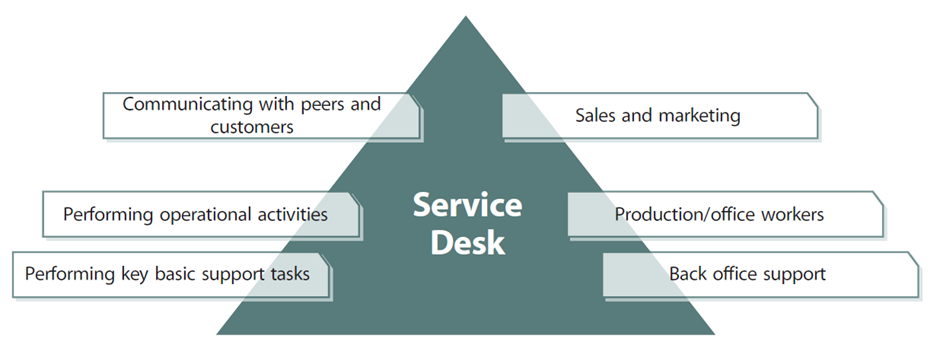

Behl (2009, p. 492) states the purpose of service operations is to “deliver agreed levels of service to users and customers, and to manage the applications, technology and infrastructure that support delivery of the services.”. To do this IT requires a customer facing aspect; this is the service desk, set up to handle direct enquires from customers and users utilising services, an example is presented in figure 6.

By improving asset capabilities and the four elements of warranty ITSMs will be driving value and eliminating waste, this can be achieved by managing daily operations.

This involves monitoring, maintaining and improving the IT service operations falling under one of the following headings.

- Event Management

- Incident Management

- Problem Management

- Request Fulfilment

- Access Management

Under ITIL each should be documented, categorised and prioritised.

7.1. Event Management

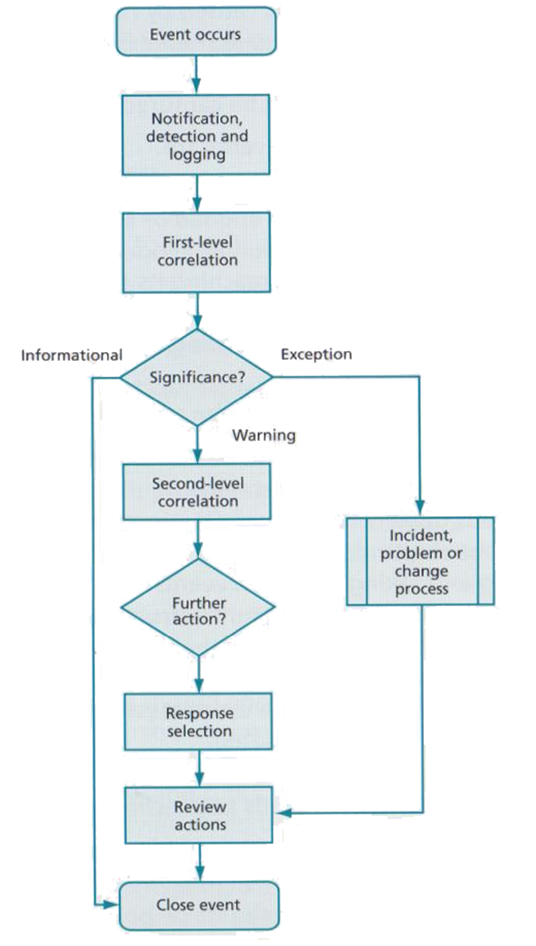

Events can occur throughout an IT infrastructure and are typically significant for management to provide a holistic view of occurrences, monitoring normal and abnormal operation. Following ITIL figure 7, a process can flag an info event that provides detail on normal operation, warnings where something might be a concern but continued normally and exceptions which have may have caused abnormal behaviours to what is expected and may require further exploration of the cause. Exceptions have the potential to be escalated to incidents or problems depending on the scope and regularity of the error (Steinberg, 2012, pp. 31-33).

7.2. Incident Management

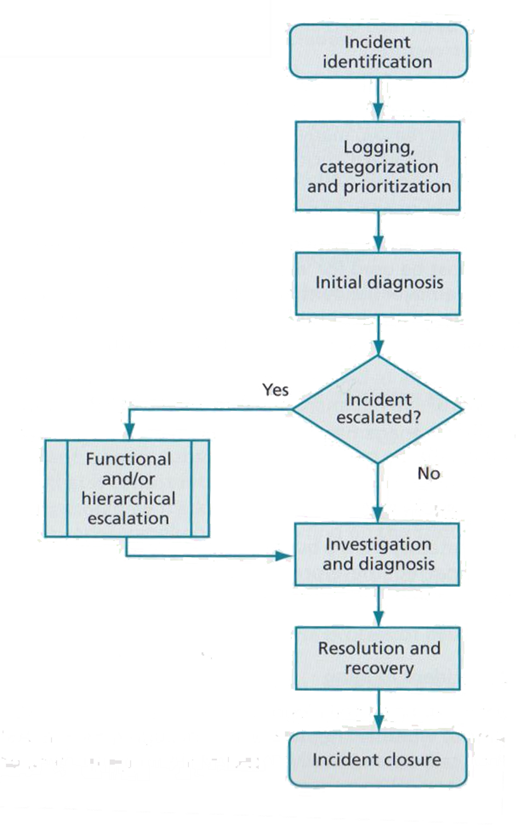

Incidents are classified as major service interruptions such a server going down, which is typically unavoidable and unplanned, characteristically caused by a fault or error. Depending on the redundancy in place and the impact to operations, incidents will normally take a high priority status to resume normal service. If an incident is severe enough it may escalate to be an emergency, crisis or disaster (Steinberg, 2012, pp. 39-41). ITIL provides figure 8.

Walker (2016) associated a cost value for each level of incident to which the business was more reactive.

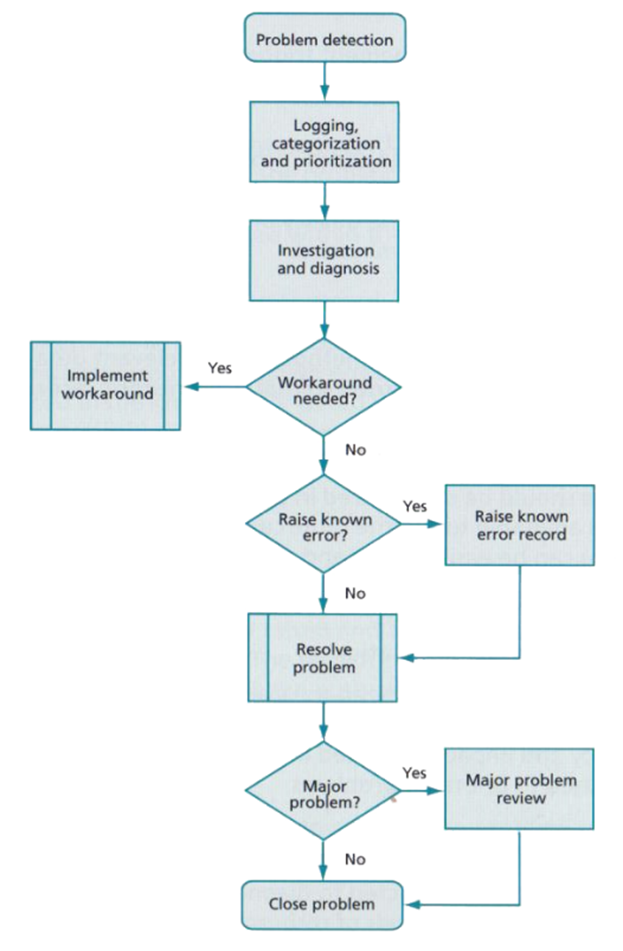

7.3. Problem Management

Problems are the underlying issues that are the root cause of individual or multiple incidents. Problem management’s primary objective is to proactively prevent problems and the resulting incidents or mitigate the impact of unpreventable incidents before they can occur again. However, problem management can also be reactive in response to one or more incidents (Steinberg, 2012, pp. 57-60).

Walker (2016) stated “in terms of importance, ITIL’s continual cycle of improvement is second only to problem management”, figure 9, and fixing underlying problems helped Liverpool Victoria reduce monthly incident costs by over £7m.

By managing problems ITSMs can:

- reduce the number and duration of incidents providing higher availability

- resolve incidents quicker and reduce unplanned labour costs

- reduce expenditure

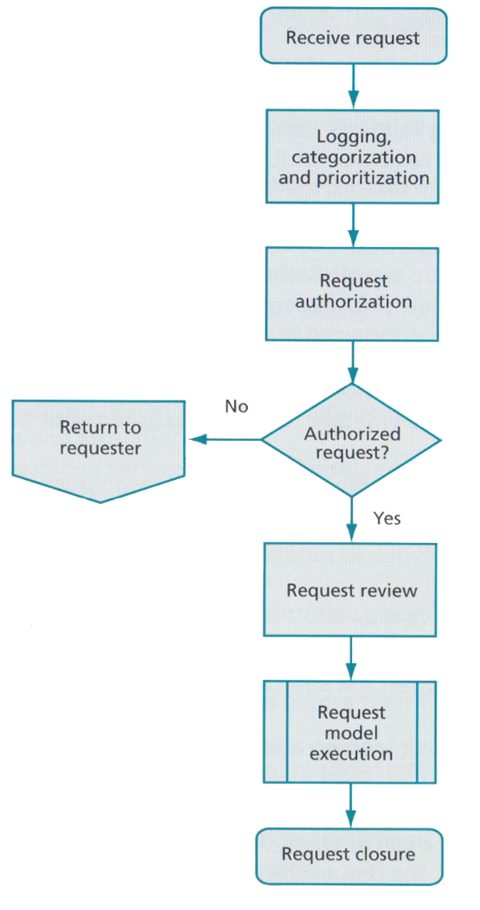

7.4. Request Fulfilment

During day to day operations ITSMs must deal with customers and users asking for modifications, examples being equipment, technology or existing solutions. These requests must be managed carefully via the service desk and prioritised to ensure that the changes proposed correctly meet the needs of the business (Steinberg, 2012, pp. 49-51), ITIL suggests figure 10.

Berengoy (2016) explained that it can be difficult to categorise requests for change (RFC) when interacting with users. If this is not captured correctly it can result in the incorrect handling of requests and incidents providing inaccurate management data. Ultimately this incurs additional costs to process and is wasteful.

RFC are discussed in more detail in sections 8-9.

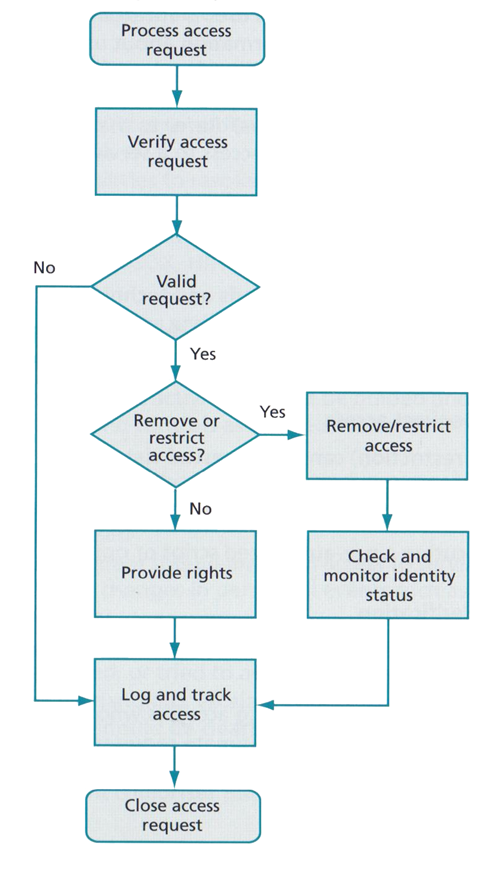

7.5. Access Management

This is ensuring that the correct people have the right access and permissions at the right times, enabling them to do their job. This includes securing the systems to ensure anyone who should not have access doesn’t, for instance if an employee was to leave the company removing any accounts or access rights that person may have had (Steinberg, 2012, pp. 67-69). ITIL provides figure 11.

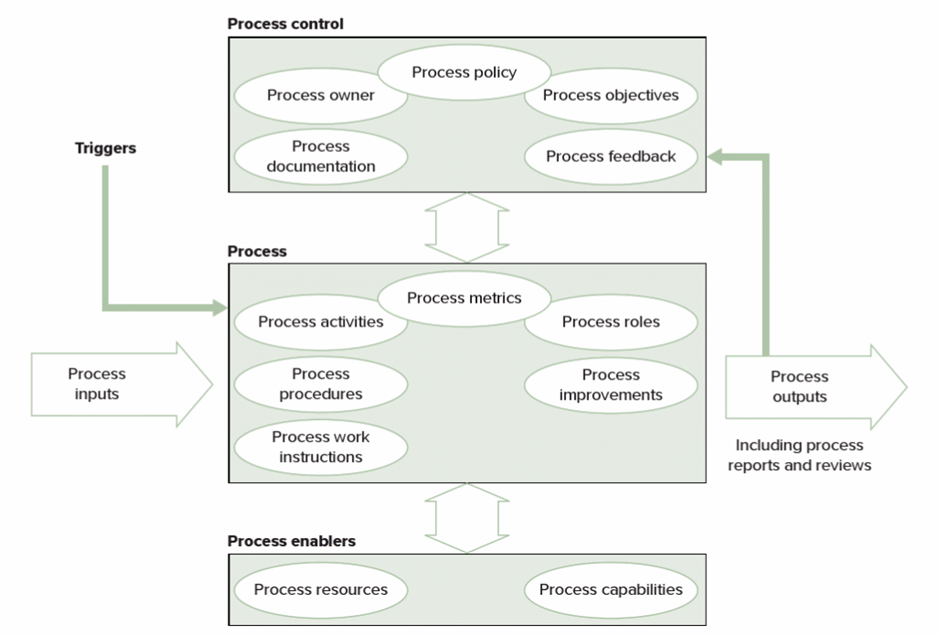

8. Measuring for Success

To improve IT services an understanding must be in place of how to handle certain situations, operations or problems. These devised sets of rules are known as business processes and can make up a part or the whole of a service. A service catalogue should be employed detailing a list of current, planned and retired services (Steinberg, 2012, pp. 13-20)

Gallacher and Morris (2012, p. 14) state that ITIL defines a process as the following:

“A Process is a structured set of activities designed to accomplish a specific objective. A process takes one or more defined inputs and turns them into defined outputs.”

To manage and control any service you need to be able to measure what the good the bad and the ugly look like. The “normal” needs to be established, the standard benchmark of operation and this will be set from the business objectives. Once the benchmark output has been established a process can be managed (Gallacher & Morris, 2012, p. 15).

“You can’t manage what you can’t measure.” – Accredited to Peter Drucker

Processes should standardise the workflow and when documented will help make proprietary asset knowledge less abundant and more company available (Walker, 2016).

Figure 12 displays ITILs process model, defining key considerations when implementing or reviewing a process. Gallacher & Morris (2012, p. 16) point out that “if no specific result is produced from following a process the question must be asked ‘should the process be taking place at all?’”.

Changes to business processes should be managed carefully to mitigate risks which may have a negative impact on capacity or availability for current services or planned future changes (Manwani, 2008).

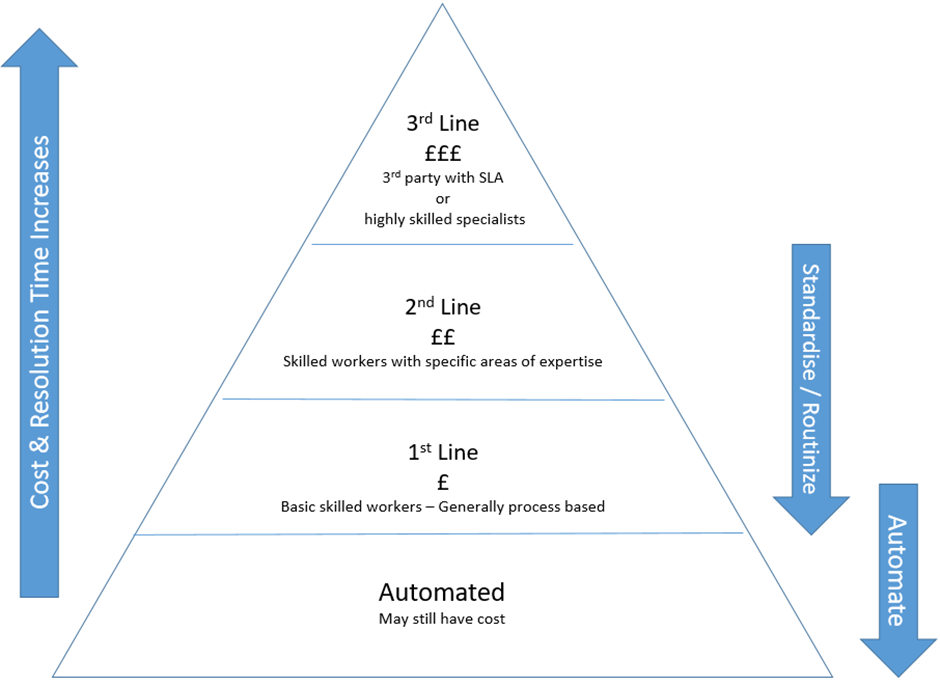

Systems such as TopDesk are available to help facilitate manage service desks and standardise reporting procedures. Berengoy (2016) explained TopDesk and ITIL is employed to a degree at West Suffolk Collage (WSC), separating incident reporting from RFC, with statistics displayed graphically on a dashboard. Tickets (RFC, Incidents), first being logged, categorised and prioritised then being assigned typically to first line support where the ticket is solved if possible. If the ticket is still unable to be resolved it is escalated to the second line who will normally have more specialised skills. Failing that it is reported to third line, which in the case of WSC is external 3rd party suppliers. Tickets under WSC are managed using KPIs, for example time to close, frequency and total open tickets.

Each of these service levels has an associated cost, Walker (2016) stated “ideally all RFC and incidents would be a first line fix every time, but this is not always possible”. With proper documentation and management information, standardisation of processes can occur, then routinized and possibly automated, figure 13. This will drive down costs utilising less expensive assets, time spent moving a ticket through the process and ultimately improving the service to the customer as they save time waiting for a fix.

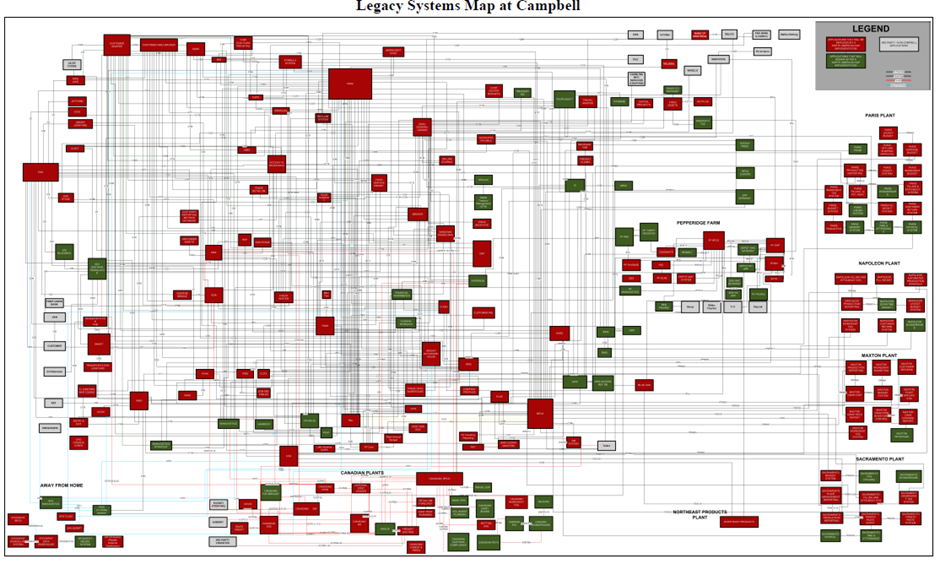

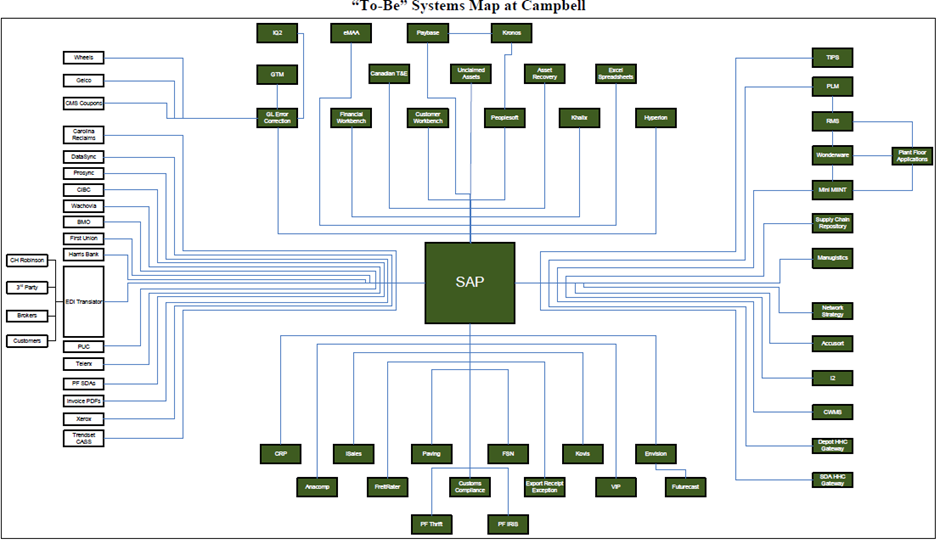

Campbells (Ross & Beath, 2008, p. 6) demonstrated system standardisation using S.A.P. moving from the unstructured overview figure 14 to standardised figure 15.

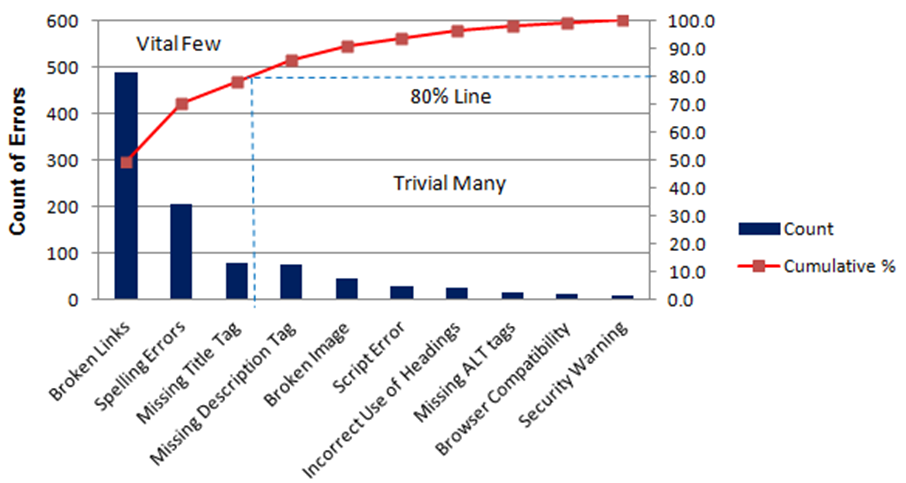

Another tool is the statistical Pareto analysis, providing an easy to view graph of event or activity frequency. Example in figure 16. Working to the 80% / 20% rule that the top 20% most frequent activities make up 80% of the workload. Focusing on the top 20% will have the greatest benefit in value generation (Galloway, 2014).

However, ITSMs must remain mindful of what they are measuring and to what level of granularity. Diluting the data set or not having enough data on the right measurement might make it difficult to understand the corrective direction required to improve. Equally managing meaningless data is also wasteful.

9. Change – A risky business?

Change is an everyday occurrence and will largely be in response to a RFC or generated from an incident, problem or access management change, covered in ITILs transition stage. These could be small in nature or companywide and global.

Change involves risks, that might negatively impact the business. The change management process is designed to minimise these risks. TopDesk’s (no date, p. 6) definition is “allow changes to be introduced into the live environment in a controlled fashion that minimizes disruption and maximizes efficiency”. If change is not managed correctly it could spell disaster for a plan and prove extremely costly. Walker (2016) stressed “Risk management underpins everything”.

Rowley (2016) outlined that requests for change will normally be passed to a Change Advice Board (CAB) for evaluation against current business goals and objectives. The CAB for Havebury is made up of people from all aspects of the business including company executive, finance, human resources and a person of impartiality towards technology, thus creating value buy in from all viewpoints. This helps to lessen risks associated with changes implemented and reduces the risk of impacting on existing ongoing projects.

Rowley (2016) outlined an international company that didn’t perform enough research and didn’t engage robust leadership with the people in its workforce to gain their buy in. Subsequently the company failed to roll out the plan and ultimately cost the company millions to back out.

In the case of Surrey Police’s failed ITC SIREN project (Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner for Surrey, 2014, p. 2) costs amounted to £14.86m.

When change is managed correctly as in the cases of Campbells Soup (Ross & Beath, 2008), Pepsi Americas (Beath & Ross, 2010) or UPS (Ross, et al., 2002), the benefits can be huge. These companies consulted the workforce at key stages ensuring that people that would be most affected by the changes would have enough training and understood why the changes were happening. These companies have all used a continual cycle of learning and improvement during the respective changes and have seen significant ROI.

9.1. Types of Change

Change should be categorised and prioritised by the acting ITSM. Three potential forms are looked at below.

9.1.1. Standard change

Can be actioned in a routine everyday manor where there are standardised or routine processes in place to handle the change and no authorisation is required. There will be minimal impact to the business and or service provided to the customer.

9.1.2. Normal change

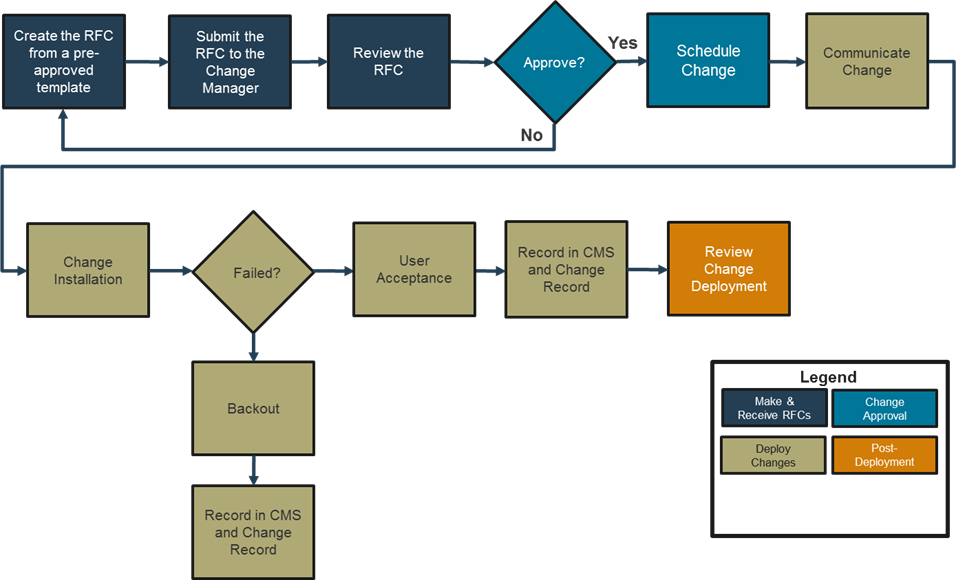

Will have an impact and will need to go through the proper assessment and authorisation channels, potentially going through a CAB before implementation. Figure 17 provides an example.

9.1.3. Emergency change

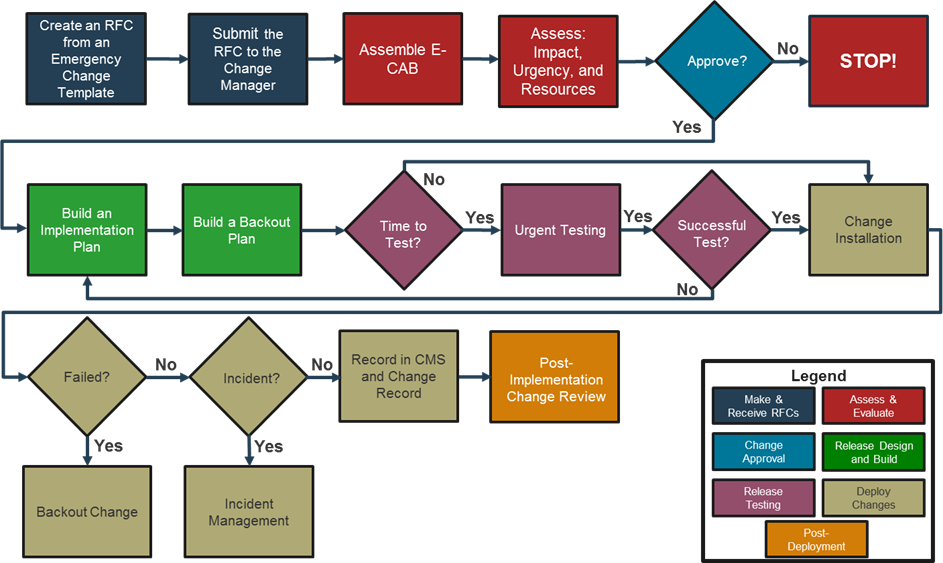

In response to a major incident impacting service provision. Whilst still following a structured process it will normally bypass some of more formal stages of the change process and allow select individuals to act accordingly allowing for a fast-reactive response. Figure 18 provides an example.

However, if it all goes wrong there needs to be the option to back out, having a rollback plan for any change may just save the day!

10. Conclusion

Change is inevitable for businesses that are innovating and improving services to stay ahead of competition and deliver market leading value. By using best practise to guide business strategy new and existing services can be managed and improved with proven success. ITIL provides reliable guides at all stages of service to help manage, maintain and improve whilst mitigating associated risks during change and innovation. ITSMs must consider roles, capabilities, resources, costs and project buy in if people are to be included in an effective and efficient implementation of change. Value is different when viewed from alternative perspectives and ITSMs must make sure they align with the business goals, typically in terms of monetary costs, for that value to be realised at all levels.

References

Barnes, C., Blake, H. & Pinder, D. (2009) Creating and Delivering Your Value Proposition: Managing Customer Experience for Profit. Kogan Page Publishers.

Beath, C. M. & Ross, J. W. (2010) PepsiAmericas: building an information savvy company.

Behl, R. (2009) Information Technology for Management. Tata McGraw Hill Education Private Limited.

Berengoy, R. (2016) West Suffolk College IT Service Desk. [Lecture to BSc (Hons) Applied Computing] BMDACP301-16S1D: IT Strategy and Change. University of Suffolk. 22 November

Cannon, D., (2011) ITIL® Service Strategy. London: The Stationery Office.

Deming Institute (no date) PDSA Cycle.Available at: https://deming.org/management-system/pdsacycle

(Accessed: 6 December 2016).

Fry, M. (2008) Building an ITIL-based service management department. Stationery Office.

Gallacher, L. & Morris, H. (2012) ITIL Foundation Exam Study Guide. 1st ed. Sybex.

Galloway, S. M. (2014) Finding Focus: A Transformational Pareto Analysis. Professional safety, 7(59), pp. 52-53.

Haughey, D. (no date) Pareto

Analysis Step By Step.

Available at: https://www.projectsmart.co.uk/pareto-analysis-step-by-step.php

(Accessed: 20 November 2016).

International Organization for Standardization – ISO

(2014) Shanghai Shuguang

Hospital, China.

Available at: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/standards/benefitsofstandards/benefits-detail.htm?emid=621

(Accessed: 19 November 2016).

Manwani, S. (2008) IT-Enabled Business Change: Successful Management. 1st ed. BCS.

McKeen, J. D. & Smith, H. (2008) IT Strategy in Action. New Jersey: Pearson Education.

Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner for Surrey

(2014) Termination of the

SIREN ICT project: Q&A.

Available at: http://www.surrey-pcc.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Public-QA-PDF1.pdf

(Accessed: 22 November 2016).

Ross, J. W. & Beath, C. (2008) Campbell Soup Company: Harmonizing Processes and Empowering Workers. MIT Sloan School Of Management: Center for Information System Research.

Ross, J. W., Draper, W., Kang, P., Schuler, S., Gozum, O. and Tolle, J. (2002) United Parcel Services: Business Transformation through Information Technology. MIT Sloan Management.

Rowley, P., (2016) ITSM, Change & Change management experiences at Havebury Housing. [Lecture to BSc (Hons) Applied Computing] BMDACP301-16S1D: IT Strategy and Change. University of Suffolk. 8 November.

SFIA Foundation, (no date) Framework summary.

Available at: https://www.sfia-online.org/en/sfia-6

(Accessed: 20 November 2016).

Steinberg, R. (2012) Key Element Guide: ITIL Service Operation. Norwich: The Stationary Office.

Steinberg, R. (2016) High Velocity ITSM: Agile IT Service Management for Rapid Change in a World of Devops, Lean IT and Cloud Computing:Trafford Publishing.

TopDesk, (no date) Change

Management Standard Operating Procedure.

Available at: http://pages.topdesk.com/rs/230-FHZ-563/images/it-Change-Management-Standard-Operating-Procedure.docx?aliId=247178

(Accessed: 26 November 2016).

Walker, D. (2016) ITSM & ITIL: Covering experiences with Liverpool Victoria Insurance. [Lecture to BSc (Hons) Applied Computing] BMDACP301-16S1D: IT Strategy and Change. University of Suffolk. 5 December.